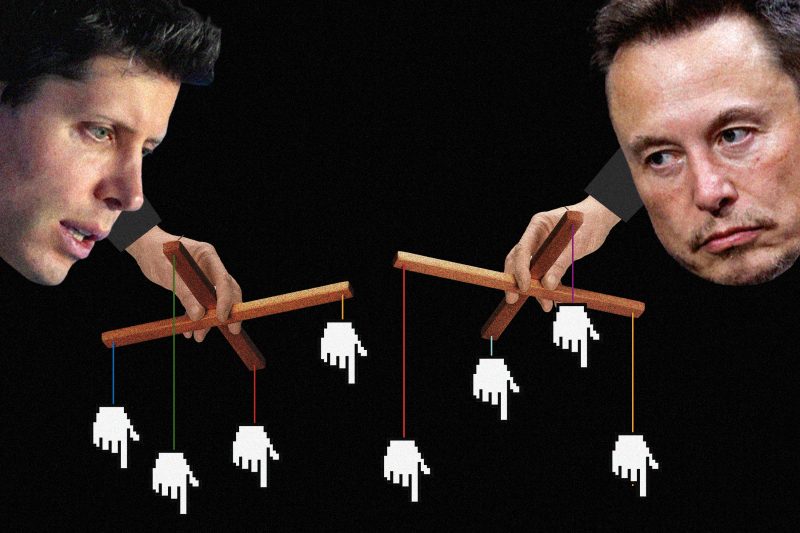

The mutiny inside OpenAI over the firing and un-firing of chief executive Sam Altman, and the implosion of X under owner Elon Musk, are not just Silicon Valley soap operas. They’re reminders: A select few make the decisions inside these society-shaping platforms, and money drives it all.

The two companies built devoted followings by promising to build populist technology for a changing world: X, formerly known as Twitter, with its global village of conversations, and OpenAI, the research lab behind ChatGPT, with its super-intelligent companions for human thought.

But under Musk and Altman, the firms largely consolidated power within a small cadre of fellow believers and loyalists who deliberate in secrecy and answer to no one.

Musk has run X as a fiefdom, boosting far-right supporters, antagonizing advertisers and attacking advocacy groups. And Altman, who was fired by the board last week and reinstated late Tuesday, has just as much, if not more, power than when he left — including a newly redrawn board from which most of the directors who opposed him have been excluded.

“These are technologies that are supposed to be so democratized and universal, but they’re so heavily influenced by one person,” said Noah Giansiracusa, a professor at Bentley University in Massachusetts who researches AI. “Everything they do is [framed as] a step toward much larger greatness and the transformation of society. But these are just cults of personality. They sell a product.”

The twin dramas that have captured the tech world’s attention are ongoing. X is still seeing advertisers leave — including, most recently, Paris Hilton’s company, whom X chief Linda Yaccarino recently championed as proof the company is still culturally relevant. And while Altman is back at OpenAI, the final composition of its nine-member board remains unknown.

Both X and OpenAI in recent months have cast themselves not just as providers of software tools but as beacons of ideologies, building tools for the long-term public good.

Musk said he bought Twitter last year for $44 billion to fight against the “woke mind virus” of liberal ideas that he said “will destroy civilization” and to safeguard it as a “digital town square” for free speech. “We’re a company that believes in transparency,” making “a single application that encompasses everything,” he said during an internal meeting last month.

As part of his crusade, Musk fired thousands of employees, kneecapped competitors, funded far-right influencers, sued an advocacy group and endorsed antisemitic theories — leading not just users to flee, but also some of its biggest advertisers, who once accounted for practically all of its revenue. Apple, Disney, IBM, Sony and other firms halted their spending this month after Musk promoted the idea that Jewish people hold a “dialectical hatred against whites.”

OpenAI has, since its founding in 2015, operated as a kind of collectivist nonprofit, an unconventional structure it said was necessary for its “humanity-scale endeavor pursuing broad benefit for humankind.” And Altman told Congress in May that it was “essential that a technology as powerful as AI is developed with democratic values in mind.”

After the board fired Altman last week, saying he’d not been “consistently candid,” more than 700 of OpenAI’s 770 employees vowed to defect unless the board resigned — perhaps to join him at Microsoft, the Big Tech behemoth that offered to hire him to lead a new advanced AI research team. Altman’s allies flooded X with lionizing messages and heart emojis in the days before the company announced his return as CEO.

In an X post on Wednesday, Altman said, “I love OpenAI, and everything I’ve done over the past few days has been in service of keeping this team and its mission together.”

The company said Wednesday that the directors who backed his firing — including the board’s only two women, Helen Toner and Tasha McCauley, proponents of a Silicon Valley dogma known as “effective altruism” — had been replaced by two members of the elite of American tech and finance. Neither are considered members of the rebel class.

Bret Taylor, a veteran Google and Facebook executive who as Twitter’s chairman pushed that board to accept Musk’s takeover, will join as chairman. In a LinkedIn post last year, Taylor championed modern AI’s “excitement and inevitability,” saying it “will change the course of every industry.”

Larry Summers, the former treasury secretary and Harvard University president who once suggested that women pursued high-level math and science less often than men because of innate differences between the sexes, is the other new board member. (Summers has said the comments were misinterpreted.)

Summers is known as an outspoken AI booster, saying in TV interviews over the last year that ChatGPT would “replace what doctors do” and that AI “could be the most important general purpose technology since the wheel or fire.” But some critics in Washington have slammed Summers for his recent off-target predictions around inflation.

Jeff Hauser, the head of the left-leaning advocacy group Revolving Door Project, said in a statement Wednesday that Summers’s role on the board was a sign OpenAI was “unserious” about its oversight, and that it “should accelerate concerns that AI will be bad for all but the richest and most opportunistic amongst us.” A Summers representative did not respond to requests for comment.

The American tech industry has long paid reverence to its monolithic slate of founders and visionaries: Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg; Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin; Apple’s Steve Jobs and Tim Cook. But where the other firms sold phones and search engines, Musk and Altman championed their work as a public mission for protecting mankind, with a for-profit business attached. It is notable that as private companies, they don’t have to report to federal regulators or to shareholders, who can vote down proposals or push back against their work.

Altman and Musk are not the only ones in Silicon Valley to claim their businesses are motivated by mission and not ego and profits. Kyle Vogt, the former head of the autonomous-vehicle company Cruise, told The Washington Post that his driverless vehicles would ultimately lead to safer roadways and brushed off any criticism of his cars as “sensationalism,” despite several episodes of disarray on San Francisco’s streets.

Former employees and public officials warned the driverless cars were not ready for widespread deployment, but Vogt justified the aggressive rollout with claims that the company, which is owned by General Motors, was morally superior to a profit-driven business.

“We have a sense of urgency but … it’s not because we’re chasing some profit targets,” he said in September. “It’s because we’re constantly reminded of the chaos on our roads every day. And we feel that now that there is finally a technology solution that can actually do something about it.”

Vogt resigned this weekend, less than a month after California revoked Cruise’s license to operate and its entire nationwide fleet was recalled, following an incident in which one of the cars dragged a struck pedestrian for 20 feet.

The corporate storytelling that pushes technology as a force for public harmony has proved to be one of Silicon Valley’s great marketing tools, said Margaret O’Mara, a professor at the University of Washington who studies the history of technology. But it’s also obscured the dangers of centralizing power and subjecting it to leaders’ personal whims.

“Silicon Valley has for years adopted this messaging and mood that it’s all about radical transparency and openness — remember Google’s ‘Don’t be evil’ motto? — and this idea of a kinder, gentle capitalism that’s going to change the world for the better,” she said.

“Then you have these moments of reckoning and remember: It’s capitalism. Some tech billionaires lost, and some other ones are winning,” she added. “These are private-sector people making money off something that serves a public function. And when they take a turn because of very personal, very individual decisions, where a handful of people are shaping the trajectory of these companies, maybe even the existence of these companies, that’s something new we all have to deal with.”

Congress’s failure to pass broad regulations on AI has only contributed to the risks. Rep. Ro Khanna, who represents parts of Silicon Valley, said in an interview that the OpenAI turmoil underscores concerns that “a few people, no matter how talented, no matter how knowledgeable, can’t be making the rules for a society on a technology that is going to have such profound consequences.”

The California Democrat, who attended a private dinner with Altman and dozens of other lawmakers in May when the tech mogul testified on Capitol Hill, said he worried that he and other tech executives were beginning to develop an “air of congresspeople and senators” that allowed them to play an outsize role in the federal debate over industry rules.

“We’ve seen a parade of these big tech leaders come to D.C.,” Khanna said. “I think highly of them, but they’re not the ones who should be leading the conversation on the regulatory framework, what safeguards we need.”

Musk and Altman share a relish for the spotlight. After suing the liberal advocacy group Media Matters for a report showing how ads on X sometimes appeared alongside pro-Nazi content, Musk on Tuesday posted a message, under a picture of him holding a katana, saying, “There is a large graveyard filled with my enemies. I do not wish to add to it, but will if given no choice.”

On Wednesday, an official X account posted about a separate report on X misinformation from NewsGuard, a fact-checking start-up, and warned news organizations against taking the findings at face value.

Altman, too, seemed to take his own victory lap as the rebellion against the OpenAI board grew. On Sunday, when he met with board members at the company’s office about a possible return, he posted a selfie to X in which he held up an OpenAI guest lanyard. “First and last time I ever wear one of these,” he wrote in the post, which has been liked more than 100,000 times.

But not everyone is so convinced that a wealthy tech luminary will save the day. After Altman’s firing, his allies began sharing a mantra across social media designed to push back on the board: “OpenAI is nothing without its people.” When an X employee sought to co-opt the message by posting “X is also nothing without its people,” Lara Cohen — a former executive there who left during Musk’s companywide purge — added her own corrective.

“Oh god,” she wrote on Threads. “Who is going to tell him?”

Cristiano Lima, Trisha Thadani and Nitasha Tiku contributed to this report.